Chapter 16: GUI Applications¶

The C implementation of Python comes with Tcl/TK for writing Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs). On Jython, the GUI toolkit that you get automatically is Swing, which comes with the Java Platform. Like CPython, there are other toolkits available for writing GUIs in Jython. Since Swing is available on any modern Java installation, we will focus on the use of Swing GUIs in this chapter.

Swing is a large subject, and can’t really be covered in a single chapter. In fact there are entire books devoted to the subject. I will provide some introduction to Swing, but only enough to describe the use of Swing from Jython. For in depth coverage of Swing, one of the many books or web tutorials should be used. [FJW: some suggested books/tutorials?].

Using Swing from Jython has a number of advantages over the use of Swing in Java. For example, bean properties are less verbose in Jython, and binding actions in Jython is much less verbose (in Java anonymous classes are typically used, in Jython a function can be passed).

Let’s start with an simple Swing application in Java, then we will look at the same application in Jython.

import java.awt.event.ActionEvent;

import java.awt.event.ActionListener;

import javax.swing.JButton;

import javax.swing.JFrame;

public class HelloWorld {

public static void main(String[] args) {

JFrame frame = new JFrame("Hello Java!");

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

frame.setSize(300, 300);

JButton button = new JButton("Click Me!");

button.addActionListener(

new ActionListener() {

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent event) {

System.out.println("Clicked!");

}

}

);

frame.add(button);

frame.setVisible(true);

}

}

This simple application draws a JFrame that is completely filled with a JButton. When the button is pressed, “Clicked!” prints out on the command line.

Now let’s see what this program looks like in Jython

from javax.swing import JButton, JFrame

frame = JFrame('Hello, Jython!',

defaultCloseOperation = JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE,

size = (300, 300)

)

def change_text(event):

print 'Clicked!'

button = JButton('Click Me!', actionPerformed=change_text)

frame.add(button)

frame.visible = True

Except for the title, the application produces the same JFrame with JButton, outputting “Clicked!” when the button is clicked.

Let’s go through the Java and the Jython examples line by line to get a feel for the differences between writing Swing apps in Jython and Java. First the import statements:

In Java

import java.awt.event.ActionEvent;

import java.awt.event.ActionListener;

import javax.swing.JButton;

import javax.swing.JFrame;

In Jython

from javax.swing import JButton, JFrame

In Jython, it is always best to have explicit imports by name, instead of using

from javax.swing import *

for the reasons covered in Chapter 7. Note that we did not need to import ActionEvent or ActionListener, since Jython’s dynamic typing allowed us to avoid mentioning these classes in our code.

Next, we have some code that creates a JFrame, and then sets a couple of bean properties.

- In Java ::

- JFrame frame = new JFrame(“Hello Java!”); frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE); frame.setSize(300, 300);

In Jython

frame = JFrame('Hello, Jython!',

defaultCloseOperation = JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE,

size = (300, 300)

)

In Java a new JFrame is created, then the bean properties defaultCloseOperation and size are set. In Jython, we are able to add the bean property setters right in the call to the constructor. This shortcut is covered in detail in chapter [FJW]? already. Still, it will bare some repeating here, since bean properties are so important in the Swing libraries. In short, if you have a getters and setters of the form getFoo/setFoo, you can treat them as properties of the object with the name “foo”. So instead of x.getFoo() you can use x.foo. Instead of x.setFoo(bar) you can use x.foo = bar. If you take a look at any Swing app above a reasonable size, you are likely to see large blocks of setters like:

JTextArea t = JTextArea();

t.setText(message)

t.setEditable(false)

t.setWrapStyleWord(true)

t.setLineWrap(true)

t.setAlignmentX(Component.LEFT_ALIGNMENT)

t.setSize(300, 1)

which, in my opinion, look better in the idiomatic Jython property setting style:

t = JTextArea()

t.text = message

t.editable = False

t.wrapStyleWord = True

t.lineWrap = True

t.alignmentX = Component.LEFT_ALIGNMENT

t.size = (300, 1)

Or rolled into the constructor:

t = JTextArea(text = message,

editable = False,

wrapStyleWord = True,

lineWrap = True,

alignmentX = Component.LEFT_ALIGNMENT,

size = (300, 1)

))

One thing to watch out for when you use properties rolled into the constructor, is that you don’t know the order in which the setters will be called. Generally this is not a problem, as the bean properties are not usually order dependant. The big exception to this is setVisible(), you probably want to set the visible property outside of the constructor to avoid any strangeness while the properties are being set. Going back to our short example, the next block of code creates a JButton, and binds the button to an action that prints out “Clicked!”.

In Java

JButton button = new JButton("Click Me!");

button.addActionListener(

new ActionListener() {

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent event) {

System.out.println("Clicked!");

}

}

);

frame.add(button);

In Jython

def change_text(event):

print 'Clicked!'

button = JButton('Click Me!', actionPerformed=change_text)

frame.add(button)

I think Jython’s method is particularly nice here when compared to Java. Here we can pass a first class function “change_text” directly to the JButton in it’s constructore, in place of the more cumbersome Java “addActionListener” method where we need to create an anonymous ActionListener class and define it’s actionPerfomed method with all of the ceremony of the static type declarations. This is one case where Jython’s readibility really stands out. Finally, in both examples we set the visible property to True. Again, although we could have set this property in the frame constructor, the visible property is one of those rare order-dependant properties that we want to set at the right time (in this case, last).

In Java

frame.setVisible(true);

In Jython

frame.visible = True

Now that we have looked at a simple example, it makes sense to see what a medium sized app might look like in Jython. Since Twitter apps have become the “Hello World” of GUI applications these days, we will go with the trend. The following application gives the user a log in prompt. When the user successfully logs in the most recent tweets in their timeline are displayed. Here is the code:

import twitter

import re

from javax.swing import (BoxLayout, ImageIcon, JButton, JFrame, JPanel,

JPasswordField, JLabel, JTextArea, JTextField, JScrollPane,

SwingConstants, WindowConstants)

from java.awt import Component, GridLayout

from java.net import URL

from java.lang import Runnable

class JyTwitter(object):

def __init__(self):

self.frame = JFrame("Jython Twitter")

self.frame.defaultCloseOperation = WindowConstants.EXIT_ON_CLOSE

self.loginPanel = JPanel(GridLayout(0,2))

self.frame.add(self.loginPanel)

self.usernameField = JTextField('',15)

self.loginPanel.add(JLabel("username:", SwingConstants.RIGHT))

self.loginPanel.add(self.usernameField)

self.passwordField = JPasswordField('', 15)

self.loginPanel.add(JLabel("password:", SwingConstants.RIGHT))

self.loginPanel.add(self.passwordField)

self.loginButton = JButton('Log in',actionPerformed=self.login)

self.loginPanel.add(self.loginButton)

self.message = JLabel("Please Log in")

self.loginPanel.add(self.message)

self.frame.pack()

self.frame.visible = True

def login(self,event):

self.message.text = "Attempting to Log in..."

self.frame.show()

username = self.usernameField.text

try:

self.api = twitter.Api(username, self.passwordField.text)

self.timeline(username)

self.loginPanel.visible = False

self.message.text = "Logged in"

except:

self.message.text = "Log in failed."

raise

self.frame.size = 400,800

self.frame.show()

def timeline(self, username):

timeline = self.api.GetFriendsTimeline(username)

self.resultPanel = JPanel()

self.resultPanel.layout = BoxLayout(self.resultPanel, BoxLayout.Y_AXIS)

for s in timeline:

self.showTweet(s)

scrollpane = JScrollPane(JScrollPane.VERTICAL_SCROLLBAR_AS_NEEDED,

JScrollPane.HORIZONTAL_SCROLLBAR_NEVER)

scrollpane.preferredSize = 400, 800

scrollpane.viewport.view = self.resultPanel

self.frame.add(scrollpane)

def showTweet(self, status):

user = status.user

p = JPanel()

# image grabbing seems very expensive, good place for a callback?

p.add(JLabel(ImageIcon(URL(user.profile_image_url))))

p.add(JTextArea(text = status.text,

editable = False,

wrapStyleWord = True,

lineWrap = True,

alignmentX = Component.LEFT_ALIGNMENT,

size = (300, 1)

))

self.resultPanel.add(p)

if __name__ == '__main__':

JyTwitter()

This code depends on the python-twitter package. This package can be found on the Python package index (PyPi). If you have easy_install (see chapter ? for instructions on easy_install) then you can install python-twitter like this:

jython easy_install python-twitter

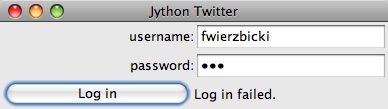

This will automatically install python-twitter’s dependancy: simplejson. Now you should be able to run the application. You should see the following login prompt:

If you put in the wrong password, you should see:

And finally, once you have successfully logged in, you should see something like this:

The constructor creates the outer frame, imaginatively called self.frame. We set defaultCloseOperation so that the app will terminate if the user closes the main window. We then create a loginPanel that holds the text fields for the user to enter username and password, and create a login button that will call the self.login method when clicked. We then put a “Please log in ” label in and make the frame visible.

def __init__(self):

self.frame = JFrame("Jython Twitter")

self.frame.defaultCloseOperation = WindowConstants.EXIT_ON_CLOSE

self.loginPanel = JPanel(GridLayout(0,2))

self.frame.add(self.loginPanel)

self.usernameField = JTextField('',15)

self.loginPanel.add(JLabel("username:", SwingConstants.RIGHT))

self.loginPanel.add(self.usernameField)

self.passwordField = JPasswordField('', 15)

self.loginPanel.add(JLabel("password:", SwingConstants.RIGHT))

self.loginPanel.add(self.passwordField)

self.loginButton = JButton('Log in',actionPerformed=self.login)

self.loginPanel.add(self.loginButton)

self.message = JLabel("Please Log in")

self.loginPanel.add(self.message)

self.frame.pack()

self.frame.visible = True

The login method changes the label text and calls into python-twitter to attempt a login. It’s in a try/excpet block that will display “Log in failed” if something goes wrong. A real application would check different types of excpetions to see what went wrong and change the display message accordingly.

def login(self,event):

self.message.text = "Attempting to Log in..."

self.frame.show()

username = self.usernameField.text

try:

self.api = twitter.Api(username, self.passwordField.text)

self.timeline(username)

self.loginPanel.visible = False

self.message.text = "Logged in"

except:

self.message.text = "Log in failed."

raise

self.frame.size = 400,800

self.frame.show()

If the login succeeds, we call the timeline method, which populates the frame with the latest tweets that the user is following. In the timeline method, we call GetFriendsTimeline from the python-twitter API, then we iterate through the status objects and call showTweet on each. All of this gets dropped into a JScrollPane and set to a reasonable size, then added to the main frame.

def timeline(self, username):

timeline = self.api.GetFriendsTimeline(username)

self.resultPanel = JPanel()

self.resultPanel.layout = BoxLayout(self.resultPanel, BoxLayout.Y_AXIS)

for s in timeline:

self.showTweet(s)

scrollpane = JScrollPane(JScrollPane.VERTICAL_SCROLLBAR_AS_NEEDED,

JScrollPane.HORIZONTAL_SCROLLBAR_NEVER)

scrollpane.preferredSize = 400, 800

scrollpane.viewport.view = self.resultPanel

self.frame.add(scrollpane)

In the showTweet method, we go through the tweets and add a a JLabel with the user’s icon (fetched by url from user.profile_image_url) and a JTextArea to contain the text of the tweet. Note all of the bean properties that we set to get the JTextArea to display correctly.

def showTweet(self, status):

user = status.user

p = JPanel()

# image grabbing seems very expensive, good place for a callback?

p.add(JLabel(ImageIcon(URL(user.profile_image_url))))

p.add(JTextArea(text = status.text,

editable = False,

wrapStyleWord = True,

lineWrap = True,

alignmentX = Component.LEFT_ALIGNMENT,

size = (300, 1)

))

self.resultPanel.add(p)

And that concludes our quick tour of Swing from Jython. Again, Swing is a very large subject, so you’ll want to look into some more dedicated Swing resources to really get a handle on it. After this chapter, it should be reasonably straightforward to translate the Java examples you find into Jython examples.