Chapter 14: Web Applications with Django¶

Django is one of the modern Python web frameworks which redefined the web niche in the Python world. A full stack approach, pragmatic design and superb documentation are some of the reason for its success.

If fast web development using the Python language sounds good to you, then fast web development using the Python language and with integration with the whole Java world (which has a strong presence on the enterprise web space) sounds even better. Running Django on Jython allows you to do just that!

And for the Java world, having Django as an option to quickly build web applications while still having the chance to use the existing Java APIs and technologies is very attractive.

In this chapter we will start with a quick introduction to have Django running with your Jython installation in a few steps and then we will build a simple web application to get a feeling of the framework. Later on, in the second half of the chapter we will take a look at the many opportunities of integration between Django web applications and the JavaEE world.

Getting Django¶

Strictly, to use Django with Jython you only need to get Django itself, and nothing more. But, without third-party libraries, you won’t be able to connect to any database, since the built-in Django database backends depend of libraries written in C, which aren’t available on Jython.

In practice, you will need at least two packages: Django itself and “django-jython”, which, as you can imagine, is a collection of Django addons that can be quite useful if you happen to be running Django on top of Jython. In particular it includes database backends, which is something you definitely need to fully appreciate the power of Django.

Since the process of getting these two libraries slightly varies depending on your platform, and it’s a manual, boring task, we will use an utility to automatically grab and install these libraries. The utility is called “setuptools”. Refer to the appendix A for instructions on how to install setuptools on Jython.

After installing setuptools the easy_install command will be

available. Armed with this we proceed to install Django:

$ easy_install Django==1.0.3

Note

I’m assuming that the bin directory of the Jython installation is on your

PATH. If it’s not, you will have to explicitly type that path preceding

each command like jython or easy_install with that path (i.e., you

will need to type something like /path/to/jython/bin/easy_install instead

of just easy_install)

By reading the output of easy_install you can see how it is doing all the

tedious work of locating the right package, downloading and installing it:

Searching for Django==1.0.3

Reading http://pypi.python.org/simple/Django/

Reading http://www.djangoproject.com/

Reading http://www.djangoproject.com/download/1.0.1-beta-1/tarball/

Best match: Django 1.0.3

Downloading http://media.djangoproject.com/releases/1.0.3/Django-1.0.3.tar.gz

Processing Django-1.0.3.tar.gz

Running Django-1.0.3/setup.py -q bdist_egg --dist-dir

/tmp/easy_install-nTnmlU/Dj ango-1.0.3/egg-dist-tmp-L-pq4s

zip_safe flag not set; analyzing archive contents...

Unable to analyze compiled code on this platform.

Please ask the author to include a 'zip_safe' setting (either True or False)

in the package's setup.py

Adding Django 1.0.3 to easy-install.pth file

Installing django-admin.py script to /home/lsoto/jython2.5.0/bin

Installed /home/lsoto/jython2.5.0/Lib/site-packages/Django-1.0.3-py2.5.egg

Processing dependencies for Django==1.0.3

Finished processing dependencies for Django==1.0.3

Then we install django-jython:

$ easy_install django-jython

Again, you will get an output similar to what you’ve seen in the previous cases. Once this is finished, you are ready.

If you want to look behind the scenes, take a look at the Lib/site-packages

subdirectory inside your Jython installation and you will entries for the

libraries we just installed. Those entries are also listed on the

easy-install.pth file, making them part of sys.path by default.

Just to make sure that everything went fine, start jython and try the following statements, which import the top-level packages of Django and django-jython:

>>> import django

>>> import doj

If you don’t get any error printed out on the screen, then everything is OK. Let’s start our first application.

A Quick Tour of Django¶

Note

If you are already familiar with Django, you won’t find anything specially new in the rest of this section. Feel free to jump to J2EE deployment and integration to look at what’s really special if you run Django on Jython.

Django is a full-stack framework. That means that it features cover from communication to the database, to URL processing and web page templating. As you may know, there are complete books which cover Django in detail. We aren’t going to go into much detail, but we are going to touch many of the features included in the framework, so you can get a good feeling of its strengths in case you haven’t had the chance to know or try Django in the past. That way you will know when Django is the right tool for a job.

The only way to take a broad view of such a resourceful framework like Django is to build something really simple with it, and then gradually augment it as we look into what the framework offers. So, we will start following roughly what the official Django tutorial uses (a simple site for polls) to extend it later to touch most of the framework features. In other words: most of the code you will see in this section comes directly from the great Django tutorial you can find on http://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.0/intro/tutorial01/.

Now, as I said on the previous paragraph, Django handles the communication with the database. Right now, the more solid backend in existence for Django/Jython is the one for PostgreSQL. So I encourage you to install PostgreSQL on your machine and setup an user and an empty database to use it in the course of this tour.

Starting a Project (and an “App”)¶

Django projects, which are usually meant to be complete web sites (or “sub-sites”) are composed of a settings file, a URL mappings file and a set of “apps” which provide the actual features of the web site. As you surely have realized, many web sites share a lot of features: administration interfaces, user authentication/registration, commenting systems, news feeds, contact forms, etc. That’s why Django decouples the actual site features in the “app” concept: apps are meant to be reusable between different projects (sites).

As we will start small, our project will consist of only one app at first. We will call our project “pollsite”. So, let’s create a clean new directory for what we will build on this sections, move to that directory and run:

$ django-admin.py startproject pollsite

And a python package named “pollsite” will be created under the directory you

created previously. At this point, the most important change we need to make

to the default settings of our shiny new project is to fill the information so

Django can talk to the database we created for this tour. So, open the file

pollsite/settings.py with your text editor of choice and change lines

starting with DATABASE with something like this:

DATABASE_ENGINE = 'doj.backends.zxjdbc.postgresql'

DATABASE_NAME = '<the name of the empty database you created>'

DATABASE_USER = '<the name of the user with R/W access to that database>'

DATABASE_PASSWORD = '<the password of such user>'

With this, you are telling Django to use the PostgreSQL driver provided by the

doj package (which, if you remember from the Getting Django section, was

the package name of the django-jython project) and to connect with the given

credentials. Now, this backend requires the PostgreSQL JDBC driver, which you

can download at http://jdbc.postgresql.org/download.html.

Once you download the JDBC driver, you need to add it to the Java

CLASSPATH. An way to do it in Linux/Unix/MacOSX for the current

session is:

$ export CLASSPATH=$CLASSPATH:/path/to/postgresql-jdbc.jar

If you are on Windows, the command is different:

$ set CLASSPATH=%CLASSPATH%:\path\to\postgresql-jdbc.jar

Done that, we will create the single app which will be the core of our

project. Make sure you are into the pollsite directory and run:

$ jython manage.py startapp polls

This will create the basic structure of a Django app. Note that the app was

created inside the project package, so we have the pollsite project and the

pollsite.polls app.

Now we will see what’s inside a Django app.

Models¶

In Django, you define your data schema in Python code, using Python classes. This central schema is used to generate the needed SQL statements to create the database schema, and to dynamically generate SQL queries when you manipulate objects of these special Python classes.

Now, in Django you don’t define the schema of the whole project in a single central place. After all, since apps are the real providers of features, it follows that the schema of the whole project isn’t more that the combination of the schemas of each app. By the way, we will switch to Django terminology now, and instead of talking about data schemas, we will talk about models (which are actually a bit more than just schemas, but the distinction is not important at this point).

If you look into the pollsite/polls directory, you will see that there is a

models.py file, which is where the app’s models must be defined. The

following code contains the model for simple polls, each poll containing many

choices:

from django.db import models

class Poll(models.Model):

question = models.CharField(max_length=200)

pub_date = models.DateTimeField('date published')

def __unicode__(self):

return self.question

class Choice(models.Model):

poll = models.ForeignKey(Poll)

choice = models.CharField(max_length=200)

votes = models.IntegerField()

def __unicode__(self):

return self.choice

As you can see, the map between a class inheriting from models.Model and a

database table is clear, and its more or less obvious how each Django field

would be translated to a SQL field. Actually, Django fields can carry more

information than SQL fields can, as you can see on the pub_date field which

includes a description more suited for human consumption: “date

published”. Django also provides more specialized field for rather common types

seen on today web applications, like EmailField, URLField or

FileField. They free you from having to write the same code again and again

to deal with concerns such as validation or storage management for the data

these fields will contain.

Once the models are defined, we want to create the tables which will hold the

data on the database. First, you will need to add app to the project settings

file (yes, the fact that the app “lives” under the project package isn’t

enough). Edit the file pollsite/settings.py and add 'pollsite.polls'

to the INSTALLED_APPS list. It will look like this:

INSTALLED_APPS = (

'django.contrib.auth',

'django.contrib.contenttypes',

'django.contrib.sessions',

'django.contrib.sites',

'pollsite.polls',

)

Note

As you see, there were a couple of apps already included in your project. These apps are included on every Django project by default, providing some of the basic features of the framework, like sessions.

After that, we make sure we are located on the project directory and run:

$ jython manage.py syncdb

If the database connection information was correctly specified, Django will

create tables and indexes for our models and for the models of the other apps

which were also included by default on INSTALLED_APPS. One of these extra

apps is django.contrib.auth, which handle user authentication. That’s why

you will also be asked for the username and password for the initial admin user for

your site:

Creating table auth_permission

Creating table auth_group

Creating table auth_user

Creating table auth_message

Creating table django_content_type

Creating table django_session

Creating table django_site

Creating table polls_poll

Creating table polls_choice

You just installed Django's auth system, which means you don't have any

superusers defined.

Would you like to create one now? (yes/no):

Answer yes to that question, and provide the requested information:

Username (Leave blank to use u'lsoto'): admin

E-mail address: admin@mailinator.com

Warning: Problem with getpass. Passwords may be echoed.

Password: admin

Warning: Problem with getpass. Passwords may be echoed.

Password (again): admin

Superuser created successfully.

After this, Django will continue mapping your models to RDBMS artifacts, creating some indexes for your tables:

Installing index for auth.Permission model

Installing index for auth.Message model

Installing index for polls.Choice model

If we want to know what’s doing Django behind the scenes, we can ask that, using

the sqlall management command (which are how the commands recognized by

manage.py are called, like the recently used syncdb). This command

requires an app label as argument and prints the SQL statements corresponding

to the models contained in the app. By the way, the emphasis on label was

intentional, as it corresponding to the last part of the “full name” of an app

and not to the full name itself. In our case, the label of “pollsite.polls” is

simply “polls”. So, we can run:

$ jython manage.py sqlall polls

And we get the following output:

BEGIN;

CREATE TABLE "polls_poll" (

"id" serial NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY,

"question" varchar(200) NOT NULL,

"pub_date" timestamp with time zone NOT NULL

)

;

CREATE TABLE "polls_choice" (

"id" serial NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY,

"poll_id" integer NOT NULL

REFERENCES "polls_poll" ("id") DEFERRABLE INITIALLY DEFERRED,

"choice" varchar(200) NOT NULL,

"votes" integer NOT NULL

)

;

CREATE INDEX "polls_choice_poll_id" ON "polls_choice" ("poll_id");

COMMIT;

Two things to note here. First, each table got an id field which wasn’t

explicitly specified on our model definition. That’s automatic, and is a

sensible default (which can be overridden if you really need a different type of

primary key, but that’s outside the scope of this quick tour). Second, see how

the sql is tailored to the particular RDBMS we are using (PostgreSQL in this

case), so naturally it may change if you use a different database backend.

OK, Let’s move on. We have our model defined, and ready to store polls. The typical next step here would be to make a CRUD administrative interface so polls can be created, edited, removed, etc. Oh, and of course we may envision some searching and filtering capabilities for this administrative, knowing in advance that once the amount of polls grow too much it will become really hard to manage.

Well, no. We won’t write this administrative interface from scratch. We will use one of the most useful features of Django: The admin app.

Bonus: The Admin¶

This is an intermission on our tour through the main architectural points of a Django project (namely: models, views and templates) but is a very nice intermission. The code for the administrative interface we talked about a couple of paragraph back will consist on less than 20 lines of code!

First, let’s enable the admin app. To do this, edit pollsite/settings.py and

add 'django.contrib.admin' to the INSTALLED_APPS. Then edit

pollsite/urls.py which looks like this:

from django.conf.urls.defaults import *

# Uncomment the next two lines to enable the admin:

# from django.contrib import admin

# admin.autodiscover()

urlpatterns = patterns('',

# Example:

# (r'^pollsite/', include('pollsite.foo.urls')),

# Uncomment the admin/doc line below and add 'django.contrib.admindocs'

# to INSTALLED_APPS to enable admin documentation:

# (r'^admin/doc/', include('django.contrib.admindocs.urls')),

# Uncomment the next line to enable the admin:

# (r'^admin/(.*)', admin.site.root),

)

And uncomment the lines which enable the admin (but not the admin/doc!), so

the file will look this way:

from django.conf.urls.defaults import *

# Uncomment the next two lines to enable the admin:

from django.contrib import admin

admin.autodiscover()

urlpatterns = patterns('',

# Example:

# (r'^pollsite/', include('pollsite.foo.urls')),

# Uncomment the admin/doc line below and add 'django.contrib.admindocs'

# to INSTALLED_APPS to enable admin documentation:

# (r'^admin/doc/', include('django.contrib.admindocs.urls')),

# Uncomment the next line to enable the admin:

(r'^admin/(.*)', admin.site.root),

)

Now you can remove all the remaining commented lines, so urls.py ends up

with the following contents:

from django.conf.urls.defaults import *

from django.contrib import admin

admin.autodiscover()

urlpatterns = patterns('',

(r'^admin/(.*)', admin.site.root),

)

I know I haven’t explained this urls.py file yet, but trust me, we will see

it in the next section.

Finally, let’s create the database artifacts needed by the admin app, running:

$ jython manage.py syncdb

Now we will see how this admin looks like. Let’s run our site in development mode by executing:

$ jython manage.py runserver

Note

The development web server is an easy way to test your web project. It will

run indefinitely until you abort it (for example, hitting Ctrl + C) and

will reload itself when you change a source file already loaded by the

server, thus giving almost instant feedback. But, be advised that using this

development server in production is a really, really bad idea.

Using a web browser, navigate to http://localhost:8000/admin/. You will

be presented with a login screen. Use the user credential you made when we first

ran syncdb in the previous section. Once you log in, you will see a page

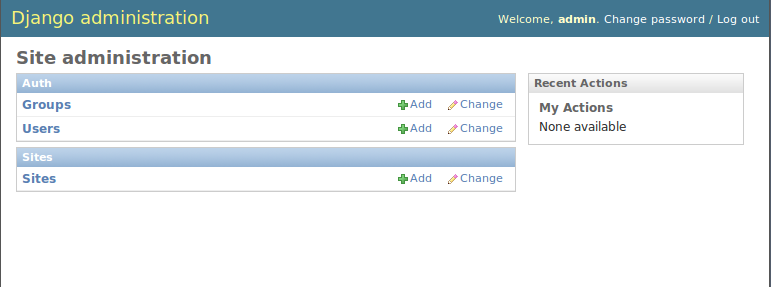

like the one shown in the figure The Django Admin.

The Django Admin

As you can see, the central area of the admin shows two boxes, titled “Auth” and “Sites”. Those boxes correspond to the “auth” and “sites” apps that are built in on Django. The “Auth” box contain two entries: “Groups” and “Users”, each one corresponding to a model contained in the auth app. If you click the “Users” link you will be presented with the typical options to add, modify and remove users. This is the kind of interfaces that the admin can provide to any other Django app, so we will add our polls app to it.

Doing so is a matter of creating an admin.py file under your app (that is,

pollsite/polls/admin.py) and declaratively telling the admin how you want to

present your models in the admin. To administer polls, the following will make

the trick:

# polls admin.py

from pollsite.polls.models import Poll, Choice

from django.contrib import admin

class ChoiceInline(admin.StackedInline):

model = Choice

extra = 3

class PollAdmin(admin.ModelAdmin):

fieldsets = [

(None, {'fields': ['question']}),

('Date information', {'fields': ['pub_date'],

'classes': ['collapse']}),

]

inlines = [ChoiceInline]

admin.site.register(Poll, PollAdmin)

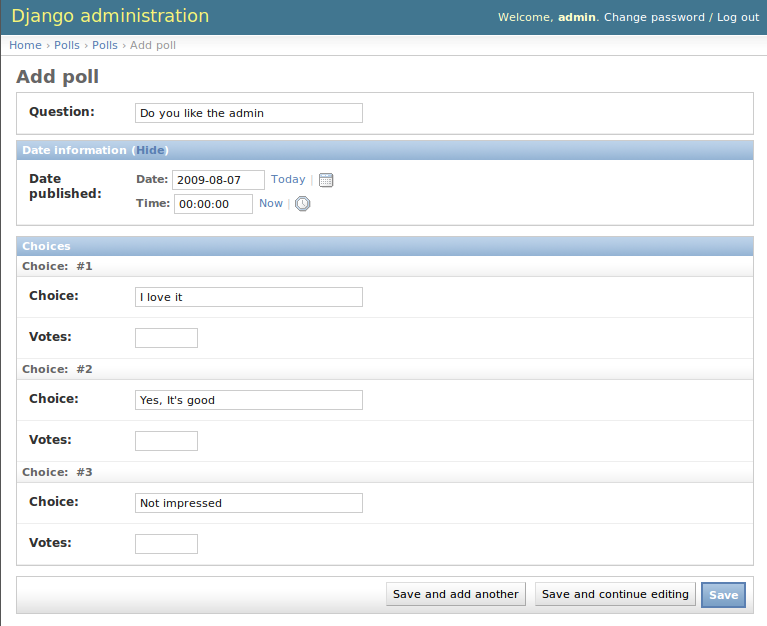

This may read like magic to you, but remember that I’m moving quick, as I want you to take a look at what’s possible to do with Django. Let’s look first at what we get after writing this code. Start the development server, go to http://localhost:8000/admin/ and see how a new “Polls” box appears now. If you click the “Add” link in the “Polls” entry, you will see a page like the one on the figure Adding a Poll using the Admin.

Adding a Poll using the Admin

Play a bit with the interface: create a couple of polls, remove one, modify

them. Note that the user interface is divided in three parts, one for the

question, another for the date (initially hidden) and other for the choices. The

first two were defined by the fieldsets of the PollAdmin class, which

let you define the titles of each section (where None means no title), the

fields contained (they can be more than one, of course) and additional CSS

classes providing behaviors like 'collapse'

It’s fairly obvious that we have “merged” the administration of our two models

(Poll and Choice) into the same user interface, since choices ought to

be edited “inline” with their corresponding poll. That was done via the

ChoiceInline class which declares what model will be inlined and how many empty

slots will be shown. The inline is hooked up into the PollAdmin later (since

you can include many inlines on any ModelAdmin class.

Finally, PollAdmin is registered as the administrative interface for the

Poll model using admin.site.register(). As you can see, everything is

absolutely declarative and works like a charm.

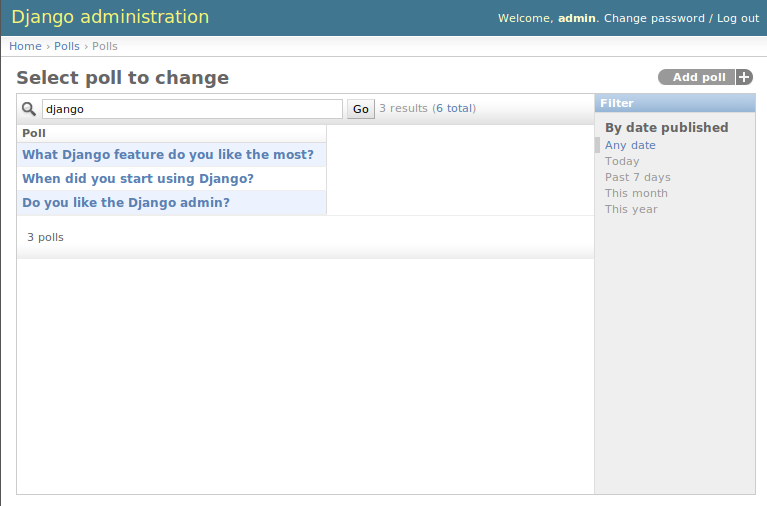

The attentive reader is probably wondering what about the search/filter features I talked about a few paragraphs back. Well, we will implement that, in the poll list interface which you can access when clicking the “Change” link for Polls in the main interface (or also by clicking the link “Polls”, or after adding a Poll).

So, add the following lines to the PollAdmin class:

search_fields = ['question']

list_filter = ['pub_date']

And play with the admin again (that’s why it was a good idea to create a few polls in the last step). The figure Searching on the Django Admin shows the search working, using “django” as the search string.

Searching on the Django Admin

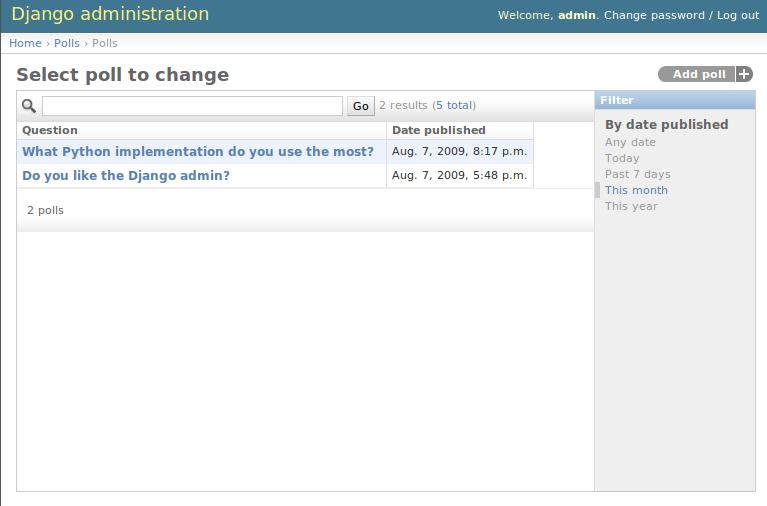

Now, if you try the filter by publishing date, it feels a bit awkward because

the list of polls only shows the name of the poll, so you can’t see what’s the

publishing date of the polls being filtered, to check if the filter worked as

advertised. That’s easy to fix, by adding the following line to the

PollAdmin class:

list_display = ['question', 'pub_date']

The figure Filtering and listing more fields on the Django Admin shows how the interface looks after all these additions.

Filtering and listing more fields on the Django Admin

Once again you can see how admin offers you all these commons features almost for free, and you only have to say what you want in a purely declarative way. However, in case you have more special needs, the admin has hooks which you can use customize its behavior. It is so powerful that sometimes it happens that a whole web application can be built based purely on the admin. See the official docs http://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.0/ref/contrib/admin/ for more information.

Views and Templates¶

Well, now that you know the admin I won’t be able to use a CRUD to showcase the rest of the main architecture of the web framework. That’s OK: CRUDs are part of almost all data driven web applications, but they aren’t what make your site different. So, now that we have delegated the tedium to the admin app, we will concentrate on polls, which is our business.

We already have our models in place, so it’s time to write our views, which are the HTTP-oriented functions that will make our app talk with the outside (which is, after all, the point of creating a web application).

Note

Django developers half-jokingly say that Django follows the “MTV” pattern: Model, Template and View. These 3 components map directly to what other modern frameworks call Model, View and Controller. Django takes this apparently unorthodox naming schema because, strictly, the controller is the framework itself. What is called “controller” code in other frameworks is really tied to HTTP and output templates, so it’s really part of the view layer. If you don’t like this viewpoint, just remember to mentally map Django templates to “views” and Django views to “controllers”.

By convention, code for views go into the app views.py file. Views are

simple functions which take an HTTP request, do some processing and return an

HTTP response. Since an HTTP response typically involves the construction of an

HTML page, templates aid views with the job of creating HTML output (and other

text-based outputs) in a more maintainable way than manually pasting strings

together.

The polls app will have a very simple navigation. First, the user will be presented with an “index” with access to the list of the latest polls. He will select one and we will show the poll “details”, that is, a form with the available choices and a button so he can submit his choice. Once a choice is made, the user will be directed to a page showing the current results of the poll he just voted on.

Before writing the code for the views: a good way to start designing a Django app is to design its URLs. In Django you map URLs to views, using regular expressions. Modern web development takes URLs seriously, and nice URLs (i.e, without cruft like “DoSomething.do” or “ThisIsNotNice.aspx”) are the norm. Instead of patching ugly names with URL rewriting, Django offers a layer of indirection between the URL which triggers a view and the internal name you happen to give to such view. Also, as Django has an emphasis on apps that can be reused across multiple projects, there is a modular way to define URLs so an app can define the relative URLs for its views, and they can be later included on different projects.

Let’s start by modifying the pollsite/urls.py file to the following:

from django.conf.urls.defaults import *

from django.contrib import admin

admin.autodiscover()

urlpatterns = patterns('',

(r'^admin/(.*)', admin.site.root),

(r'^polls/', include('pollsite.polls.urls')),

)

Note how we added the pattern which says: if the URL starts with polls/

continue mat matching it following the patters defined on module

pollsite.polls.urls. So let’s create the file pollsite/polls/urls.py

(note that it will live inside the app) and put the following code in it:

from django.conf.urls.defaults import *

urlpatterns = patterns('pollsite.polls.views',

(r'^$', 'index'),

(r'^(\d+)/$', 'detail'),

(r'^(\d+)/vote/$', 'vote'),

(r'^(\d+)/results/$', 'results'),

)

The first pattern says: If there is nothing else to match (remember that

polls/ was already matched by the previous pattern), use the index

view. The others patterns include a placeholder for numbers, written in the

regular expression as \d+, and it is captured (using the parenthesis) so it

will be passed as argument to their respective views. The end result is that an

URL like polls/5/results/ will call the results view passing the string

'5' as the second argument (the first view argument is always the

request object). If you want to know more about Django URL dispatching, see

http://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.0/topics/http/urls/.

So, from the URL patterns we just created, it can be seen that we need to write

the view functions named index, detail, vote and results. Here

is code for pollsite/polls/views.py:

from django.shortcuts import get_object_or_404, render_to_response

from django.http import HttpResponseRedirect

from django.core.urlresolvers import reverse

from pollsite.polls.models import Choice, Poll

def index(request):

latest_poll_list = Poll.objects.all().order_by('-pub_date')[:5]

return render_to_response('polls/index.html',

{'latest_poll_list': latest_poll_list})

def detail(request, poll_id):

poll = get_object_or_404(Poll, pk=poll_id)

return render_to_response('polls/detail.html', {'poll': poll})

def vote(request, poll_id):

poll = get_object_or_404(Poll, pk=poll_id)

try:

selected_choice = poll.choice_set.get(pk=request.POST['choice'])

except (KeyError, Choice.DoesNotExist):

# Redisplay the poll voting form.

return render_to_response('polls/detail.html', {

'poll': poll,

'error_message': "You didn't select a choice.",

})

else:

selected_choice.votes += 1

selected_choice.save()

# Always return an HttpResponseRedirect after successfully dealing

# with POST data. This prevents data from being posted twice if a

# user hits the Back button.

return HttpResponseRedirect(

reverse('pollsite.polls.views.results', args=(poll.id,)))

def results(request, poll_id):

poll = get_object_or_404(Poll, pk=poll_id)

return render_to_response('polls/results.html', {'poll': poll})

I know this was a bit fast, but remember that we are taking a quick tour. The

important thing here is to grasp the high level concepts. Each function defined

in this file is a view. You can identify them because, well, they are defined on

the views.py file. But perhaps more importantly, because they receive a

request as a first argument.

So, we defined the views named index, details, vote and results

which are going to be called when an URL match the patterns defined

previously. With the exception of vote, they are straightforward, and follow

the same pattern: They search some data (using the Django ORM and helper

functions like get_object_or_404 which, even if you aren’t familiar with

them it’s easy to intuitively imagine what they do), and then end up calling

render_to_response, passing the path of a template and a dictionary with the

data passed to the template.

Note

The three trivial views described above represent cases so common in web development that Django provides an abstraction to implement them with even less code. The abstraction is called “Generic Views” and you can learn about them on http://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.0/ref/generic-views/, as well as in the Django tutorial at http://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.0/intro/tutorial04/#use-generic-views-less-code-is-better

The vote view is a bit more involved, and it ought to be, since it is the

one which do interesting things, namely, registering a vote. It has two paths:

one for the exceptional case in which the user has not selected any choice and

one in which the used did select one. See how in the first case the view ends up

rendering the same template which is rendered by the detail view:

polls/detail.html, but we pass an extra variable to the template to display

the error message so the user can know why he is still viewing the same page. In

the successful case in which the user selected a choice, we increment the votes

and redirect the user to the results view.

We could have archived the redirection by just calling the view (something like

return results(request, poll.id)) but, as the comments say, is a good

practice to do an actual HTTP redirect after POST submissions to avoid

problems with the browser back button (or the refresh button). Since the view

code don’t know to what URLs they are mapped (as that is expected to chance from

site to site when you reuse the app) the reverse function gives you the URL

for a given view and parameters.

Before taking a look at templates, a note about them. The Django template

language is pretty simple and intentionally not as powerful as a programming

language. You can’t execute arbitrary python code nor call any function. It is

designed this way to keep templates simple and webdesigner-friendly. The main

features of the template language are expressions, delimited by double braces

({{ and }}), and directives (called “template tags”), delimited by

braces and the percent character ({% and %}). Expression can contain

dots which do both attribute access and item access (so you write {{ foo.bar

}} even if in Python you would write foo['bar']) and also pipes to apply

filters to the expressions (like, for example, cut a string expression at some

given maximum length). And that’s pretty much it. You see how obvious they are

on the following templates, but I’ll give a bit of explanation when introducing

some non obvious template tags.

Now, it’s time to see the templates for our views. As you can infer by reading

the views code we just wrote we need three templates: polls/index.html,

polls/detail.html and polls/results.html. We will create the

templates subdirectory inside the polls app, and then create the

templates under it. So here is the content of

pollsite/polls/templates/polls/index.html:

{% if latest_poll_list %}

<ul>

{% for poll in latest_poll_list %}

<li><a href="{{ poll.id }}/">{{ poll.question }}</a></li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

{% else %}

<p>No polls are available.</p>

{% endif %}

Pretty simple, as you can see. Let’s move to

pollsite/polls/templates/polls/detail.html:

<h1>{{ poll.question }}</h1>

{% if error_message %}<p><strong>{{ error_message }}</strong></p>{% endif %}

<form action="./vote/" method="post">

{% for choice in poll.choice_set.all %}

<input type="radio" name="choice" id="choice{{ forloop.counter }}"

value="{ { choice.id }}" />

<label for="choice{{ forloop.counter }}">{{ choice.choice }}</label><br />

{% endfor %}

<input type="submit" value="Vote" />

</form>

One perhaps surprising construct on this template is the {{ forloop.counter

}} expression, which simply exposes the internal counter the surrounding {%

for %} loop.

Also note that the {% if %} template tag will evaluate to false a expression

that is not defined, as will be the case with error_message when this

template is called from the detail view.

Finally, here is pollsite/polls/templates/polls/results.html:

<h1>{{ poll.question }}</h1>

<ul>

{% for choice in poll.choice_set.all %}

<li>{{ choice.choice }} -- {{ choice.votes }}

vote{{ choice.votes|pluralize }}</li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

In this template you can see the use of a filter, in the expression {{

choice.votes|pluralize }}. It will output an “s” if the number of votes is

greater than 1, and nothing otherwise. To learn more about the template tags

and filters available by default in Django, see

http://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.0/ref/templates/builtins/. And to know more

on how it works and how to create new filters and template tags, see

http://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.0/ref/templates/api/.

At this point we have a fully working poll site. It’s not pretty, and can use a lot of polishing. But it works! Try it navigating to http://localhost:8000/polls/.

Reusing Templates without “include”: Template Inheritance¶

Like many other template languages, Django also has a “include” directive. But it’s use is very rare, because there is a better solution for reusing templates: inheritance.

It works just like class inheritance. You define a base template, with many “blocks”. Each block has a name. Then other templates can inherit from the base template and override or extend the blocks. You are free to build inheritance chains of any length you want, just like with class hierarchies.

You may have noted that our templates weren’t producing valid HTML, but only fragments. It was convenient, to focus on the important parts of the templates, of course. But it also happens that with a very minor modification they will generate a complete, pretty HTML pages. As you probably guessed by now, they will extend from a site-wide base template.

Since I’m not exactly good with web design, we will take a ready-made template from http://www.freecsstemplates.org/. In particular, we will modify this template: http://www.freecsstemplates.org/preview/exposure/.

Note that the base template is going to be site-wide, so it belongs to the

project, not to an app. We will create a templates subdirectory under the

project directory. Here is the content for pollsite/templates/base.html:

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/ xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd">

<html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml">

<head>

<meta http-equiv="content-type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" />

<title>Polls</title>

<link rel="alternate" type="application/rss+xml"

title="RSS Feed" href="/feeds/polls/" />

<style>

/* Irrelevant CSS code, see book sources if you are interested */

</style>

</head>

<body>

<!-- start header -->

<div id="header">

<div id="logo">

<h1><a href="/polls/">Polls</a></h1>

<p>an example for the Jython book</a></p>

</div>

<div id="menu">

<ul>

<li><a href="/polls/">Home</a></li>

<li><a href="/contact/">Contact Us</a></li>

<li><a href="/admin/">Admin</a></li>

</ul>

</div>

</div>

<!-- end header -->

<!-- start page -->

<div id="page">

<!-- start content -->

<div id="content">

{% block content %} {% endblock %}

</div>

<!-- end content -->

<br style="clear: both;" />

</div>

<!-- end page -->

<!-- start footer -->

<div id="footer">

<p> <a href="/feeds/polls/">Subscribe to RSS Feed</a> </p>

<p class="legal">

©2009 Apress. All Rights Reserved.

•

Design by

<a href="http://www.freecsstemplates.org/">Free CSS Templates</a>

•

Icons by <a href="http://famfamfam.com/">FAMFAMFAM</a>. </p>

</div>

<!-- end footer -->

</body>

</html>

As you can see, the template declares only one block, named “content” (near the end of the template before the footer). You can define as many blocks as you want, but to keep things simple we will do only one.

Now, to let Django find this template we need to tweak the settings. Edit

pollsite/settings.py and locate the TEMPLATE_DIRS section. replace it

with the following:

import os

TEMPLATE_DIRS = (

os.path.dirname(__file__) + '/templates',

# Put strings here, like "/home/html/django_templates" or

# "C:/www/django/templates".

# Always use forward slashes, even on Windows.

# Don't forget to use absolute paths, not relative paths.

)

That’s a trick to avoid hardcoding the project root directory. The trick may not

work on all situations, but it will work for us. Now, that we have this

base.html template in place, we will inherit from it in

pollsite/polls/templates/polls/index.html:

{% extends 'base.html' %}

{% block content %}

{% if latest_poll_list %}

<ul>

{% for poll in latest_poll_list %}

<li><a href="{{ poll.id }}/">{{ poll.question }}</a></li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

{% else %}

<p>No polls are available.</p>

{% endif %}

{% endblock %}

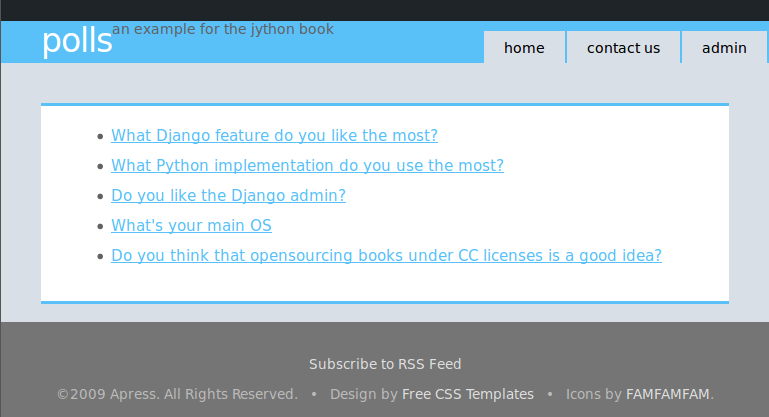

As you can see, the changes are limited to the addition of the two first lines and the last one. The practical implication is that the template is overriding the “content” block and inheriting all the rest. Do the same with the other two templates of the poll app and test the application again, visiting http://localhost:8000/polls/. It will look as shown on the figure The Poll Site After Applying a Template.

The Poll Site After Applying a Template

At this point we could consider our sample web application to be complete. But I want to highlight some other features included in Django that can help you to develop your web apps (just like the admin). To showcase them we will add the following features to our site:

- A contact form (note that the link is already included in our common base template)

- A RSS feed for the latest polls (also note the link was already added on the footer)

- User Comments on polls.

Forms¶

Django features some help to deal with HTML forms, which is always a bit tiresome. We will use this help to implement the “contact us” feature. Since it sounds like a common feature that could be reused on in the future, we will create a new app for it. Move to the project directory and run:

$ jython manage.py startapp contactus

Remember to add an entry for this app on pollsite/settings.py under the

INSTALLED_APPS list as 'pollsite.contactus'.

Then we will delegate URL matching the /contact/ pattern to the app, by

modifying pollsite/urls.py and adding one line for it:

from django.conf.urls.defaults import *

from django.contrib import admin

admin.autodiscover()

urlpatterns = patterns('',

(r'^admin/(.*)', admin.site.root),

(r'^polls/', include('pollsite.polls.urls')),

(r'^contact/', include('pollsite.contactus.urls')),

)

Later, we create pollsite/contactus/urls.py. For simplicity’s sake we will

use only one view to display and process the form. So the file

pollsite/contactus/urls.py will simply consist of:

from django.conf.urls.defaults import *

urlpatterns = patterns('pollsite.contactus.views',

(r'^$', 'index'),

)

And the contents of pollsite/contactus/views.py is:

from django.shortcuts import render_to_response

from django.core.mail import mail_admins

from django import forms

class ContactForm(forms.Form):

name = forms.CharField(max_length=200)

email = forms.EmailField()

title = forms.CharField(max_length=200)

text = forms.CharField(widget=forms.Textarea)

def index(request):

if request.method == 'POST':

form = ContactForm(request.POST)

if form.is_valid():

mail_admins(

"Contact Form: %s" % form.title,

"%s <%s> Said: %s" % (form.name, form.email, form.text))

return render_to_response("contactus/success.html")

else:

form = ContactForm()

return render_to_response("contactus/form.html", {'form': form})

The important bit here is the ContactForm class in which the form is

declaratively defined and which encapsulates the validation logic. We just call

the is_valid() method on our view to invoke that logic and act

accordingly. See http://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.0/topics/email/#mail-admins

to learn about the main_admins function included on Django and how to

adjust the project settings to make it work.

Forms also provide quick ways to render them in templates. We will try that

now. This is the code for pollsite/contactus/templates/contactus/form.html

which is the template used the the view we just wrote:

{% extends "base.html" %}

{% block content %}

<form action="." method="POST">

<table>

{{ form.as_p }}

</table>

<input type="submit" value="Send Message" >

</form>

{% endblock %}

Here we take advantage of the as_table() method of Django forms, which also

takes care of rendering validation errors. Django forms also provide other

convenience functions to render forms, but if none of them suits your need, you

can always render the form in custom ways. See

http://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.0/topics/forms/ for details on form handling.

Before testing this contact form, we need to write the template

pollsite/contactus/templates/contactus/success.html which is also used from

pollsite.contactus.views.index:: This template is quite simple:

{% extends "base.html" %}

{% block content %}

<h1> Send us a message </h1>

<p><b>Message received, thanks for your feedback!</p>

{% endblock %}

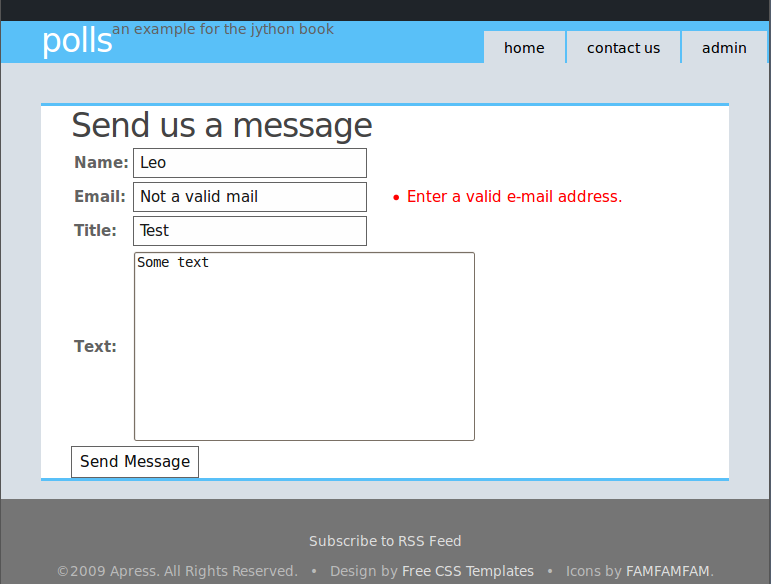

And we are done. Test it by navigation to http://localhost:8000/contact/. Try submitting the form without data, or with erroneous data (for example with an invalid email address). You will get something like what’s shown on the figure Django Form Validation in Action. Without needing to write much code you get all that validation, almost for free. Of course the forms framework is extensible, so you can create custom form field types with their own validation or rendering code. Again, I’ll refer you to http://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.0/topics/forms/ for detailed information.

Django Form Validation in Action

Feeds¶

It’s time to implement the feed we are offering on the link right before the

footer. It surely won’t surprise you to know that Django include ways to state

declaratively your feeds and write them very quickly. Let’s start by modifying

pollsite/urls.py to leave it as follows:

from django.conf.urls.defaults import *

from pollsite.polls.feeds import PollFeed

from django.contrib import admin

admin.autodiscover()

urlpatterns = patterns('',

(r'^admin/(.*)', admin.site.root),

(r'^polls/', include('pollsite.polls.urls')),

(r'^contact/', include('pollsite.contactus.urls')),

(r'^feeds/(?P<url>.*)/$', 'django.contrib.syndication.views.feed',

{'feed_dict': {'polls': PollFeed}}),

)

The changes are the import of the PollFeed class (which we haven’t wrote

yet) and the last pattern for URLs starting with /feeds/, which will map to

a built-in view which takes a dictionary with feeds as argument (in our case,

PollFeed is the only one). Writing the this class, which will describe the

feed, is very easy. Let’s create the file pollsite/polls/feeds.py and put

the following code on it:

from django.contrib.syndication.feeds import Feed

from django.core.urlresolvers import reverse

from pollsite.polls.models import Poll

class PollFeed(Feed):

title = "Polls"

link = "/polls"

description = "Latest Polls"

def items(self):

return Poll.objects.all().order_by('-pub_date')

def item_link(self, poll):

return reverse('pollsite.polls.views.detail', args=(poll.id,))

def item_pubdate(self, poll):

return poll.pub_date

And we are almost ready. When a request for the URL /feeds/polls/ is

received by Django, it will use this feed description to build all the XML

data. The missing part is how will be the content of polls displayed on the

feeds. To do this, we need to create a template. By convention, it has to be

named feeds/<feed_name>_description.html, where <feed_name> is what we

specified as the key on the feed_dict in pollsite/urls.py. Thus we

create the file pollsite/polls/templates/feeds/polls_description.html with

this very simple content:

<ul>

{% for choice in obj.choice_set.all %}

<li>{{ choice.choice }}</li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

The idea is simple: Django passes each object returned by PollFeed.items()

to this template, in which it takes the name obj. You then generate an

HTML fragment which will be embedded on the feed result.

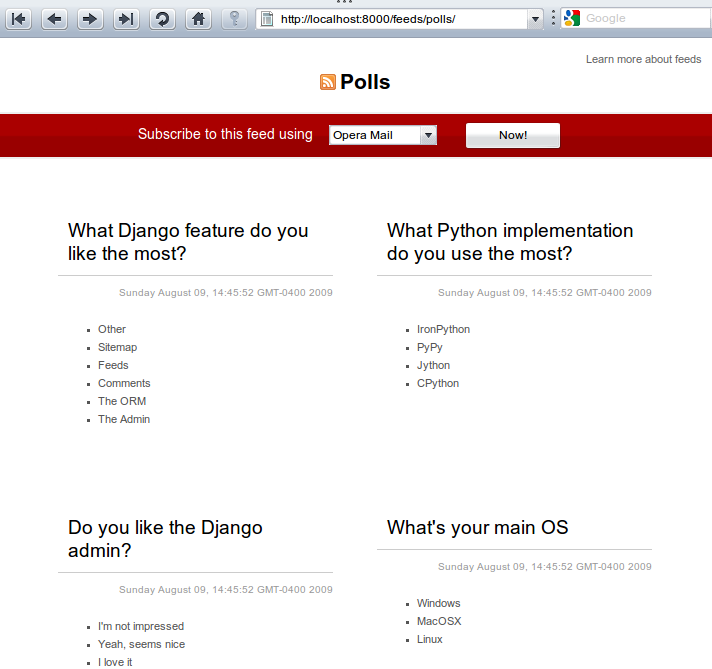

And that’s all. Test it by pointing your browser to http://localhost:8000/feeds/polls/, or by subscribing to that URL with your preferred feed reader. Opera, for example, displays the feed as shown by figure Poll feed displayed on the Opera browser

Poll feed displayed on the Opera browser

Comments¶

Since comments are a common feature of current web sites, Django includes a

mini-framework to make it easy the incorporation of comments to any project or

app. I will show you how to use it in our project. First, add a new URL pattern for

the Django comments app, so the pollsite/urls.py file will look like this:

from django.conf.urls.defaults import *

from pollsite.polls.feeds import PollFeed

from django.contrib import admin

admin.autodiscover()

urlpatterns = patterns('',

(r'^admin/(.*)', admin.site.root),

(r'^polls/', include('pollsite.polls.urls')),

(r'^contact/', include('pollsite.contactus.urls')),

(r'^feeds/(?P<url>.*)/$', 'django.contrib.syndication.views.feed',

{'feed_dict': {'polls': PollFeed}}),

(r'^comments/', include('django.contrib.comments.urls')),

)

Then, add 'django.contrib.comments' to the INSTALLED_APPS on

pollsite/settings.py. After that, we will let Django create the necessary

tables by running:

$ jython manage.py syncdb

The comments will be added to the poll page, so we must edit

pollsite/polls/templates/polls/detail.html. We will add the following code

just before the {% endblock %} line which currently is the last line of the

file:

{% load comments %}

{% get_comment_list for poll as comments %}

{% get_comment_count for poll as comments_count %}

{% if comments %}

<p>{{ comments_count }} comments:</p>

{% for comment in comments %}

<div class="comment">

<div class="title">

<p><small>

Posted by <a href="{{ comment.user_url }}">{{ comment.user_name }}</a>,

{{ comment.submit_date|timesince }} ago:

</small></p>

</div>

<div class="entry">

<p>

{{ comment.comment }}

</p>

</div>

</div>

{% endfor %}

{% else %}

<p>No comments yet.</p>

{% endif %}

<h2>Left your comment:</h2>

{% render_comment_form for poll %}

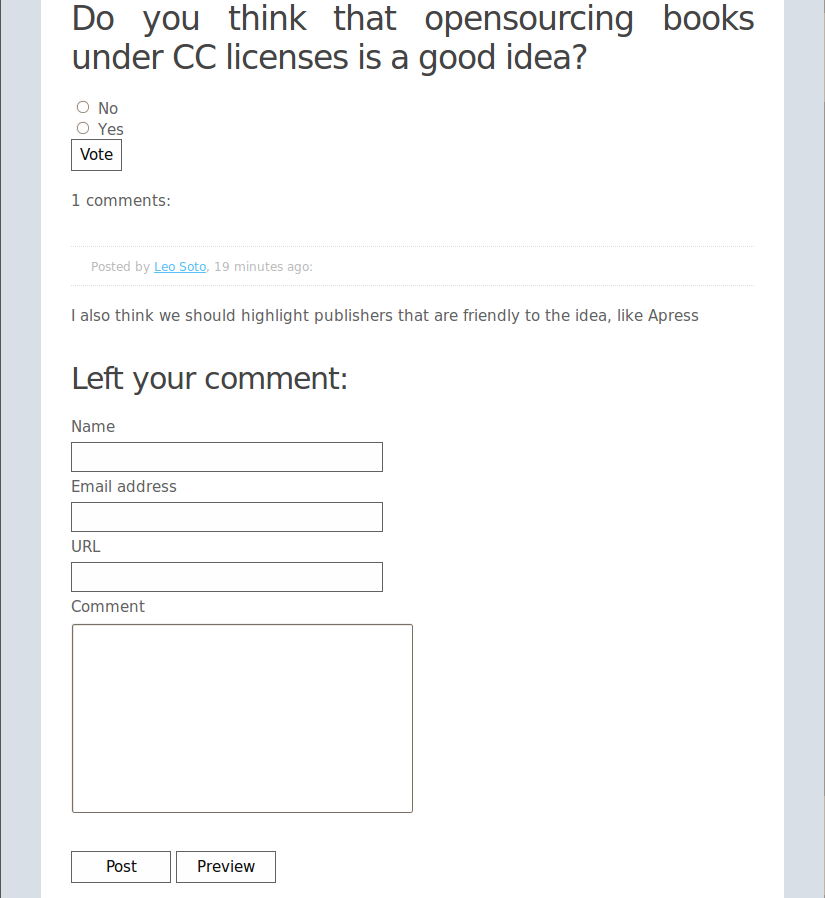

Basically, we are importing the “comments” template tag library (by doing {%

load comments %}) and then we just use it. It supports binding comments to

any database object, so we don’t need to do anything special to make it

work. The figure Comments Powered Poll shows what we get in exchange

for that short snippet of code.

Comments Powered Poll

If you try the application by yourself you will note that after submiting a

comment you get a ugly page showing the success message. Or if you don’t enter

all the data, an ugly error form. That’s because we are using the comments

templates. A quick and effective fix for that is creating the file

pollsite/templates/comments/base.html with the following content:

{% extends 'base.html' %}

Yeah, it’s only one line! It shows the power of template inheritance: all what we need was to change the base template of the comments framework to inherit from our global base template.

And more…¶

At this point I hope you have learned to appreciate Django strenghts: It’s a very good web framework in itself, but it also takes the “batteries included” philosophy and comes with solutions for many common problems in web development. This usually speed up a lot the process of creating a new website. And we didn’t touched other common topics that Django provides out of the box like user authentication (from the login dialog to easily declaring which views require an authenticated user, or an user with some special characteristic like being an site administrator), or generic views.

But this book is about Jython and we will use the rest of this chapter to show the interesting possibilities that appear when you run Django on Jython. If you want to learn more about Django itself, I recommend (again) the excellent official documentation available on http://docs.djangoproject.com/.

J2EE deployment and integration¶

Although you could deploy your application using Django’s built in development server, it’s a terrible idea. The development server isn’t designed to operate under heavy load and this is really a job that is more suited to a proper application server. We’re going to install Glassfish v2.1 - an opensource highly performant JavaEE 5 application server from Sun Microsystems and show deployment onto it.

Let’s install Glassfish now - obtain the release from

https://glassfish.dev.java.net/public/downloadsindex.html

At the time of this writing, Glassfish v3.0 is being prepared for release and it will support Django and Jython out of the box, but we’ll stick to the stable release as the documentation and stability has been well established. Download the v2.1 release (currently v2.1-b60e). I strongly suggest you use JDK6 to do your deployment.

Once you have the installation JAR file, you can install it by issuing

% java -Xmx256m -jar glassfish-installer-v2.1-b60e-windows.jar

If your glassfish installer file has a different name, just use that instead of the filename listed in the above example. Be careful where you invoke this command though - Glassfish will unpack the application server into a subdirectory ‘glassfish’ in the directory that you start the installer.

One step that tripped me up during my impatient installation of Glassfish is that you actually need to invoke ant to complete the installation. On UNIX you need to invoke

% chmod -R +x lib/ant/bin

% lib/ant/bin/ant -f setup.xml

or for Windows

% lib\ant\bin\ant -f setup.xml

This will complete the setup - you’ll find a bin directory with “asadmin” or “asadmin.bat” which will indicate that the application server has been installed.. You can start the server up by invoking

% bin/asadmin start_domain -v

On Windows, this will start the server in the foreground - the process will not daemonize and run in the background. On UNIX operating systems, the process will automatically daemonize and run in the background. In either case, once the server is up and running, you will be able to reach the web administration screen through a browser by going to http://localhost:5000/. The default login is ‘admin’ and the password is ‘adminadmin’.

Currently, Django on Jython only supports the PostgreSQL database officially, but there is a preliminary release of a SQL Server backend as well as a SQLite3 backend. Let’s get the PostgreSQL backend working - you will need to obtain the PostgreSQL JDBC driver from http://jdbc.PostgreSQL.org.

At the time of this writing, the latest version was in postgresql-8.4-701.jdbc4.jar, copy that jar file into your GLASSFISH_HOME/domains/domain/domain1/lib directory. This will enable all your applications hosted in your appserver to use the same JDBC driver.

You should now have a GLASSFISH_HOME/domains/domain1/lib directory with the following contents

applibs/

classes/

databases/

ext/

postgresql-8.3-604.jdbc4.jar

You will need to stop and start the application server to let those libraries load up.

% bin/asadmin stop_domain

% bin/asadmin start_domain -v

Deploying your first application¶

Django on Jython includes a built in command to support the creation of WAR files, but first, you will need to do a little bit of configuration you will need to make everything run smoothly. First we’ll setup a simple Django application that has the administration application enabled so that we have some models that we play with. Create a project called ‘hello’ and make sure you add ‘django.contrib.admin’ and ‘doj’ applications to the INSTALLED_APPS.

Now enable the user admin by editting urls.py and uncomment the admin lines. Your urls.py should now look something like this

from django.conf.urls.defaults import *

from django.contrib import admin

admin.autodiscover()

urlpatterns = patterns('',

(r'^admin/(.*)', admin.site.root),

)

Disabling PostgreSQL logins¶

The first thing I inevitably do on a development machine with PostgreSQL is disable authenticaion checks to the database. The fastest way to do this is to enable only local connections to the database by editting the pg_hba.conf file. For PostgreSQL 8.3, this file is typically located in c:PostgreSQL8.3datapg_hba.conf and on UNIXes - it is typically located in /etc/PostgreSQL/8.3/data/pg_hba.conf

At the bottom of the file, you’ll find connection configuration information. Comment out all the lines and enable trusted connections from localhost. Your editted configuration should look something like this

# TYPE DATABASE USER CIDR-ADDRESS METHOD

host all all 127.0.0.1/32 trust

This will let any username password to connect to the database. You do not want to do this for a public facing production server. You should consult the PostgreSQL documentation for instructions for more suitable settings. After you’ve editted the connection configuration, you will need to restart the PostgreSQL server.

Create your PostgreSQL database using the createdb command now

> createdb demodb

Setting up the database is straightforward - just enable the pgsql backend from Django on Jython. Note that backend will expect a username and password pair even though we’ve disabled them in PostgreSQL. You can populate anything you want for the DATABASE_NAME and DATABASE_USER settings. The database section of your settings module should now look something like this

DATABASE_ENGINE = 'doj.backends.zxjdbc.postgresql'

DATABASE_NAME = 'demodb'

DATABASE_USER = 'ngvictor'

DATABASE_PASSWORD = 'nosecrets'

Initialize your database now

> jython manage.py syncdb Creating table django_admin_log Creating table auth_permission Creating table auth_group Creating table auth_user Creating table auth_message Creating table django_content_type Creating table django_session Creating table django_site

You just installed Django’s auth system, which means you don’t have any superusers defined. Would you like to create one now? (yes/no): yes Username: admin E-mail address: admin@abc.com Warning: Problem with getpass. Passwords may be echoed. Password: admin Warning: Problem with getpass. Passwords may be echoed. Password (again): admin Superuser created successfully. Installing index for admin.LogEntry model Installing index for auth.Permission model Installing index for auth.Message model

All of this should be review so far, now we’re going to take the application and deploy it into the running Glassfish server. This is actually the easy part. Django on Jython comes with a custom ‘war’ command that builds a self contained file which you can use to deploy into any Java servlet container.

A note about WAR files¶

For JavaEE servers, a common way to deploy your applications is to deploy a ‘WAR’ file. This is just a fancy name for a zip file that contains your application and any dependencies it requires that the application server has not made available as a shared resource. This is a robust way of making sure that you minimize the impact of versioning changes of libraries if you want to deploy multiple applications in your app server.

Consider your Django applications over time - you will undoubtedly upgrade your version of Django, you may upgrade the version of your database drivers - you may even deciede to upgrade the version of the Jython language you wish to deploy on. These choices are ultimately up to you if you bundle all your dependencies in your WAR file. By bundling up all your dependencies into your WAR file, you can ensure that your app will “just work” when you go to deploy it. The server will automatically partition each application into its own space with concurrently running versions of the same code.

—

To enable the war command, add the ‘doj’ appplication to your settings in the INSTALLED_APPS list. Next, you will need to enable your site’s media directory and a context relative root for your media. Edit your settings.py module so that that your media files are properly configured to be served. The war command will automatically configure your media files so that they are served using a static file servlet and the URLs will be remapped to be after the context root.

Edit your settings module and configure the MEDIA_ROOT and MEDIA_URL lines.

MEDIA_ROOT = ‘c:\dev\hello\media_root’ MEDIA_URL = ‘/site_media/’

Now you will need to create the media_root subdirectory under your ‘hello’ project and drop in a sample file so you can verify that static content serving is working. Place a file “sample.html” into yoru media_root directory. Put whatever contents you want into it - we’re just using this to ensure that static files are properly served.

In english - that means when the above configuration is used - ‘hello’ will deployed into your servlet container and the container will assign some URL path to be the ‘context root’ in Glassfish’s case - this means your app will live in ‘http://localhost:8000/hello/’. The site_media directory will be visible at “http://localhost:8000/hello/site_media”. DOJ will automatically set the static content to be served by Glassfish’s fileservlet which is already highly performant. There is no need to setup a separate static file server for most deployments.

Build your war file now using the standard manage.py script, and deploy using the asadmin tool

c:\dev\hello>jython manage.py war

Assembling WAR on c:\docume~1\ngvictor\locals~1\temp\tmp1-_snn\hello

Copying WAR skeleton...

Copying jython.jar...

Copying Lib...

Copying django...

Copying media...

Copying hello...

Copying site_media...

Copying doj...

Building WAR on C:\dev\hello.war...

Cleaning c:\docume~1\ngvictor\locals~1\temp\tmp1-_snn...

Finished.

Now you can copy C:\dev\hello.war to whatever location your application server wants it.

C:\dev\hello>cd \glassfish

C:\glassfish>bin\asadmin.bat deploy hello.war

Command deploy executed successfully.

C:\glassfish>

That’s it. You should now be able to see your application running on

http://localhost:8080/hello/

The administration screen should also be visible at :

You can verify that your static media is being served correctly by going to:

That’s it. Your basic deployment to a servlet container is now working.

Extended installation¶

The war command in doj provides extra options for you to specify extra JAR files to include with your application and which can bring down the size of your WAR file. By default, the ‘war’ command will bundle the following items:

- Jython

- Django and it’s administration media files

- your project and media files

- all of your libraries in site-packages

You can specialize your WAR file to include specific JAR files and you can instruct doj to assemble a WAR file with just the python packages that you require. The respective options for “manage.py war” are “–include-py-packages” and “–include-jar-libs”. The basic usage is straight forward, simply pass in the location of your custom python packages and the JAR files to these two arguments and distutils will automatially decompress the contents of those compressed volumes and recompess them into your WAR file.

To bundle JAR files up, you will need to specify a list of files to “–include-java-libs”.

The following example bundles the jTDS JAR flie and a regular python module called urllib3 with our WAR file.:

$ jython manage.py war --include-java-libs=$HOME/downloads/jtds-1.2.2.jar \

--include-py-package=$HOME/PYTHON_ENV/lib/python2.5/site-packages/urllib3

You can have multiple JAR files or python packages listed, but you must delimit them with your operating system’s path separator. For UNIX systems - this means “:” and for Windows it is “;”.

Eggs can also be installed using “–include-py-path-entries” using the egg filename. For example

$ jython manage.py war --include-py-path-entries=$HOME/PYTHON_ENV/lib/python2.5/site-packages/urllib3

Connection pooling with JavaEE¶

Whenever your web application goes to fetch data from the database, that data has to come back over a database connection. Some databases have ‘cheap’ database connections like MySQL, but for many databases - creating and releasing connections is quite expensive. Under high load conditions - opening and closing database connections on every request can quickly consume too many file handles - and your application will crash.

The general solution to this is to employ database connection pooling. While your application will continue to create new connections and close them off, a connection pool will manage your database connections from a reusable set. When you go to close your connection - the connection pool will simply reclaim your connection for use at a later time. Using a pool means you can put an enforced upper limit restriction on the number of concurrent connections to the database. Having that upper limit means you can reason about how your application will perform when the upper limit of database connections is hit.

While Django does not natively support database connection pools with CPython, you can enable them in the PostgreSQL driver for Django on Jython. Creating a connection pool that is visible to Django/Jython is a two step process in Glassfish. First, we’ll need to create a JDBC connection pool, then we’ll need to bind a JNDI name to that pool. In a JavaEE container, JNDI - the Java Naming and Directory Interface - is a registry of names bound to objects. It’s really best thought of as a hashtable that typically abstracts a factory that emits objects.

In the case of database connections - JNDI abstracts a ConnectionFactory which provides proxy objects that behave like database connections. These proxies automatically manage all the pooling behavior for us. Lets see this in practice now.

First we’ll need to create a JDBC ConnectionFactory. Go to the administration screen of Glassfish and go down to Resources/JDBC/JDBC Resources/Connection Pools. From there you can click on the ‘New’ button and start to configure your pool.

Set the name to “pgpool-demo”, the resource type should be “javax.sql.ConnectionPoolDataSource” and the Database Vendor should be PostgreSQL. Click ‘Next’.

At the bottom of the next page, you’ll see a section with “Additional Properties”. You’ll need to set four parameters to make sure the connection is working, assuming that the database is configured for a username/password of ngvictor/nosecrets - here’s what you need to connect to your database.

| Name | Value |

|---|---|

| databaseName | demodb |

| serverName | localhost |

| password | nosecrets |

| user | ngvictor |

You can safely delete all the other properties - they’re not needed. Click ‘Finish’.

Your pool will now be visible on the left hand tree control in the Connection Pools list. Select it and try pinging it to make sure it’s working. If all is well, Glassfish will show you a successful Ping message.

We now need to bind a JNDI name to the connection factory to provide a mechanism for Jython to see the pool. Go to the JDBC Resources and click ‘New’. Use the JNDI name: “jdbc/pgpool-demo”, select the ‘pgpool-demo’ as your pool name and hit “OK”>

Verify from the command line that the resource is available

glassfish\bin $ asadmin list-jndi-entries --context jdbc

Jndi Entries for server within jdbc context:

pgpool-demo__pm: javax.naming.Reference

__TimerPool: javax.naming.Reference

__TimerPool__pm: javax.naming.Reference

pgpool-demo: javax.naming.Reference

Command list-jndi-entries executed successfully.

Now, we need to enable the Django application use the JNDI name based lookup if we are running in an application server, and fail back to regular database connection binding if JNDI can’t be found. Edit your settings.py module and add an extra configuration to enable JNDI.

DATABASE_ENGINE = 'doj.backends.zxjdbc.postgresql'

DATABASE_NAME = 'demodb'

DATABASE_USER = 'ngvictor'

DATABASE_PASSWORD = 'nosecrets'

DATABASE_OPTIONS = {'RAW_CONNECTION_FALLBACK': True, \

'JNDI_NAME': 'jdbc/pgpool-demo' }

Note that we’re duplicating the configuration to connect to the database. This is because we want to be able to fall back to regular connection binding in the event that JNDI lookups fail. This makes our life easier when we’re running in a testing or development environment.

That’s it.

You’re finished configuring database connection pooling. That wasn’t that bad now was it?

Dealing with long running tasks¶

When you’re building a complex web application, you will inevitably end up having to deal with processes which need to be processed in the background. If you’re building on top of CPython and Apache, you’re out of luck here - there’s no standard infrastructure available for you to handle these tasks. Luckily these services have had years of engineering work already done for you in the Java world. We’ll take a look at two different strategies for dealing with long running tasks.

Thread Pools¶

The first strategy is is to leverage managed thread pools in the JavaEE container. When your webapplication is running within Glassfish, each HTTP request is processed by the HTTP Service which contains a threadpool. You can change the number of threads to affect the performance of the webserver. Glassfish will also let you create your own threadpools to execute arbitrary work units for you.

The basic API for threadpools is simple:

- WorkManager which provides an abstracted interface to the thread pool

- Work is an interface which encapsulates your unit of work

- WorkListener which is an interface that lets you monitor the progress of your Work tasks.

First, we need to tell Glassfish to provision a threadpool for our use. In the Adminstration screen, go down to Configuration/Thread Pools. Click on ‘New’ to create a new thread pool. Give your threadpool the name “backend-workers”. Leave all the other settings as the default values and click “OK”.

You’ve now got a thread pool that you can use. The threadpool exposes an interface where you can submit jobs to the pool and the pool will either execute the job synchronously within a thread, or you can schedule the job to run asynchronously. As long as your unit of work implements the javax.resource.spi.work.Work interface, the threadpool will happily run your code. A unit of class may be as simple as the following snippet of code

from javax.resource.spi.work import Work

class WorkUnit(Work):

"""

This is an implementation of the Work interface.

"""

def __init__(self, job_id):

self.job_id = job_id

def release(self):

"""

This method is invoked by the threadpool to tell threads

to abort the execution of a unit of work.

"""

logger.warn("[%d] Glassfish asked the job to stop quickly" % self.job_id)

def run(self):

"""

This method is invoked by the threadpool when work is

'running'

"""

for i in range(20):

logger.info("[%d] just doing some work" % self.job_id)

This WorkUnit class above doesn’t do anything very interesting, but it does illustrate the basic structure of what unit of work requires. We’re just logging message to disk so that we can visually see the thread execute.

WorkManager implements several methods which can run your job and block until the threadpool completes your work, or it can run the job asynchronously. Generally, I prefer to run things asynchronously and simply check the status of the work over time. This lets me submit multiple jobs to the threadpool at once and check the status of each of the jobs.

To monitor the progress of work, we need to implement the WorkListener interface. This interface gives us notifications as a task progresses through the 3 phases of execution within the thread pool. Those states are :

- Accepted

- Started

- Completed

All jobs must go to either Completed or Rejected states. The simplest thing to do then is to simple build up lists capturing the events. When the length of the completed and the rejected lists together are the same as the number of jobs we submitted, we know that we are done. By using lists instead of simple counters, we can inspect the work objects in much more detail.

Here’s the code for our SimpleWorkListener

from javax.resource.spi.work import WorkListener

class SimpleWorkListener(WorkListener):

"""

Just keep track of all work events as they come in

"""

def __init__(self):

self.accepted = []

self.completed = []

self.rejected = []

self.started = []

def workAccepted(self, work_event):

self.accepted.append(work_event.getWork())

logger.info("Work accepted %s" % str(work_event.getWork()))

def workCompleted(self, work_event):

self.completed.append(work_event.getWork())

logger.info("Work completed %s" % str(work_event.getWork()))

def workRejected(self, work_event):

self.rejected.append(work_event.getWork())

logger.info("Work rejected %s" % str(work_event.getWork()))

def workStarted(self, work_event):

self.started.append(work_event.getWork())

logger.info("Work started %s" % str(work_event.getWork()))

To access the threadpool, you simply need to know the name of the pool we want to access and schedule our jobs. Each time we schedule a unit of work, we need to tell the pool how long to wait until we timeout the job and provide a reference to the WorkListener so that we can monitor the status of the jobs.

The code to do this is listed below

from com.sun.enterprise.connectors.work import CommonWorkManager

from javax.resource.spi.work import Work, WorkManager, WorkListener

wm = CommonWorkManager('backend-workers')

listener = SimpleWorkListener()

for i in range(5):

work = WorkUnit(i)

wm.scheduleWork(work, -1, None, listener)

You may notice that the scheduleWork method takes in a None in the third argument. This is the execution context - for our purposes, it’s best to just ignore it and set it to None. The scheduleWork method will return immediately and the listener will get callback notifications as our work objects pass through. To verify that all our jobs have completed (or rejected) - we simply need to check the listener’s internal lists.

while len(listener.completed) + len(listener.rejected) < num_jobs:

logger.info("Found %d jobs completed" % len(listener.completed))

time.sleep(0.1)

That covers all the code you need to access thread pools and monitor the status of each unit of work. Ignoring the actual WorkUnit class, the actual code to manage the threadpool is about a dozen lines long.

JavaEE standards and thread pools¶

Unfortunately, this API is not standard in the JavaEE 5 specification yet so the code listed here will only work in Glassfish. The API for parallel processing is being standardized for JavaEE 6, and until then you will need to know a little bit of the internals of your particular application server to get threadpools working. If you’re working with Weblogic or Websphere, you will need to use the CommonJ APIs to access the threadpools, but the logic is largely the same.

Passing messages across process boundaries¶

While threadpools provide access to background job processing, sometimes it may be beneficial to have messages pass across process boundaries. Every week there seems to be a new Python package that tries to solve this problem, for Jython we are lucky enough to leverage Java’s JMS. JMS specifies a message brokering technology where you may define publish/subscribe or point to point delivery of messages between different services. Messages are asychnronously sent to provide loose coupling and the broker deals with all manner of boring engineering details like delivery guarantees, security, durability of messages between server crashes and clustering.

While you could use a handrolled RESTful messaging implementation - using OpenMQ and JMS has many advantages.

- It’s mature. Do you really think your messaging implementation handles all the corner cases? Server crashes? Network connectivity errors? Reliability guarantees? Clustering? Security? OpenMQ has almost 10 years of engineering behind it. There’s a reason for that.

- The JMS standard is just that - standard. You gain the ability to send and receive messages between any JavaEE code.

- Interoperability. JMS isn’t the only messaging broker in town. The Streaming Text Orientated Messaing Protocol (STOMP) is another standard that is popular amongst non-Java developers. You can turn a JMS broker into a STOMP broker by using stompconnect. This means you can effectively pass messages between any messaging client and any messaging broker using any of a dozen different languages.

In JMS there are two types of message delivery mechanisms:

- Publish/Subscribe: This is for the times when we want to message one or more subscribers about events that are occuring. This is done through JMS ‘topics’.

- Point to point messaging: These are single sender, single receiver message queues. Appropriately, JMS calls these ‘queues’

We need to provision a couple objects in Glassfish to get JMS going. In a nutshell, we need to create a connection factory which clients will use to connect to the JMS broker. We’ll create a publish/subscribe resource and a point to point messaging queue. In JMS terms, there are called “destinations”. They can be thought of as postboxes that you send your mail to.

Go to the Glassfish administration screen and go to Resources/JMS Resources/Connection Factories. Create a new connection factory with the JNDI name: “jms/MyConnectionFactory”. Set the resource type to javax.jms.ConnectionFactory. Delete the username and password properties at the bottom of the screen and add a single property: ‘imqDisableSetClientID’ with a value of ‘false’. Click ‘OK’.

# TODO screenshot of the property setting

By setting the imqDisableSetClientID to false, we are forcing clients to declare a username and password when they use the ConnectionFactory. OpenMQ uses the login to uniquely identify the clients of the JMS service so that it can properly enforce the delivery guarantees of the destination.

We now need to create the actual destinations - a topic for publish/subscribe and a queue for point to point messaging. Go to Resources/JMS Resources/Destination Resources and click ‘New’. Set the JNDI name to ‘jms/MyTopic’, the destination name to ‘MyTopic’ and the Resource type to be ‘javax.jms.Topic’. Click “OK” to save the topic.

# TODO: create the topic image